80 years Freedom: Piet Roodenburgh Prodigy Hockey in the field that gave his life for resistance

On May 5, the Netherlands celebrates 80 years of freedom. Exactly 80 years after the liberation from Nazi Germany, the country once destroyed by war remembers those who fell and those who rose up during the most challenging times in its modern history.

Even under the ruthless rule of Nazi Germany, the sport kept the Dutch people. Football remained largely untouched by the occupiers and withdrew thousands of participation.

But the pits, courts and fields also housed heroes of Dutch resistance, who fought for the country’s freedom by giving shelter to Jewish families, sabotaging the efforts of the German war, being the extension of the Dutch government in London and standing against oppression.

During the week we celebrate 80 years of freedom, we tell the stories of the resistance heroes that lived double life in and outside the theater of their sport.

Episode 1: Gerben Wagenar, the Hero of Dutch Resistance who sparked his football club fire

Episode 2: Ad van eerd, the resistance hero that Captain PSV in their first title

Episode 3: Olympia, Boxing School in Amsterdam which formed the first Jewish resistance

Piet Roodenburgh

Imagine this: You are 22 years old, studying chemistry and medicine at the University of Amsterdam and a field hockey on the Dutch national team. Seed can go wrong?

Pieter Arnold Roodenburgh, or JUST PIET, was the son of Alida Van de Koppel and Daan Roodenburgh. Daan Daan is a prominent name in Ajax’s history as the designer of his first two stadiums – Houten Stadion and Stadion de Meer, who was his home stadium between 1934 and 1996 – and as a club player and commissar in the 1930s.

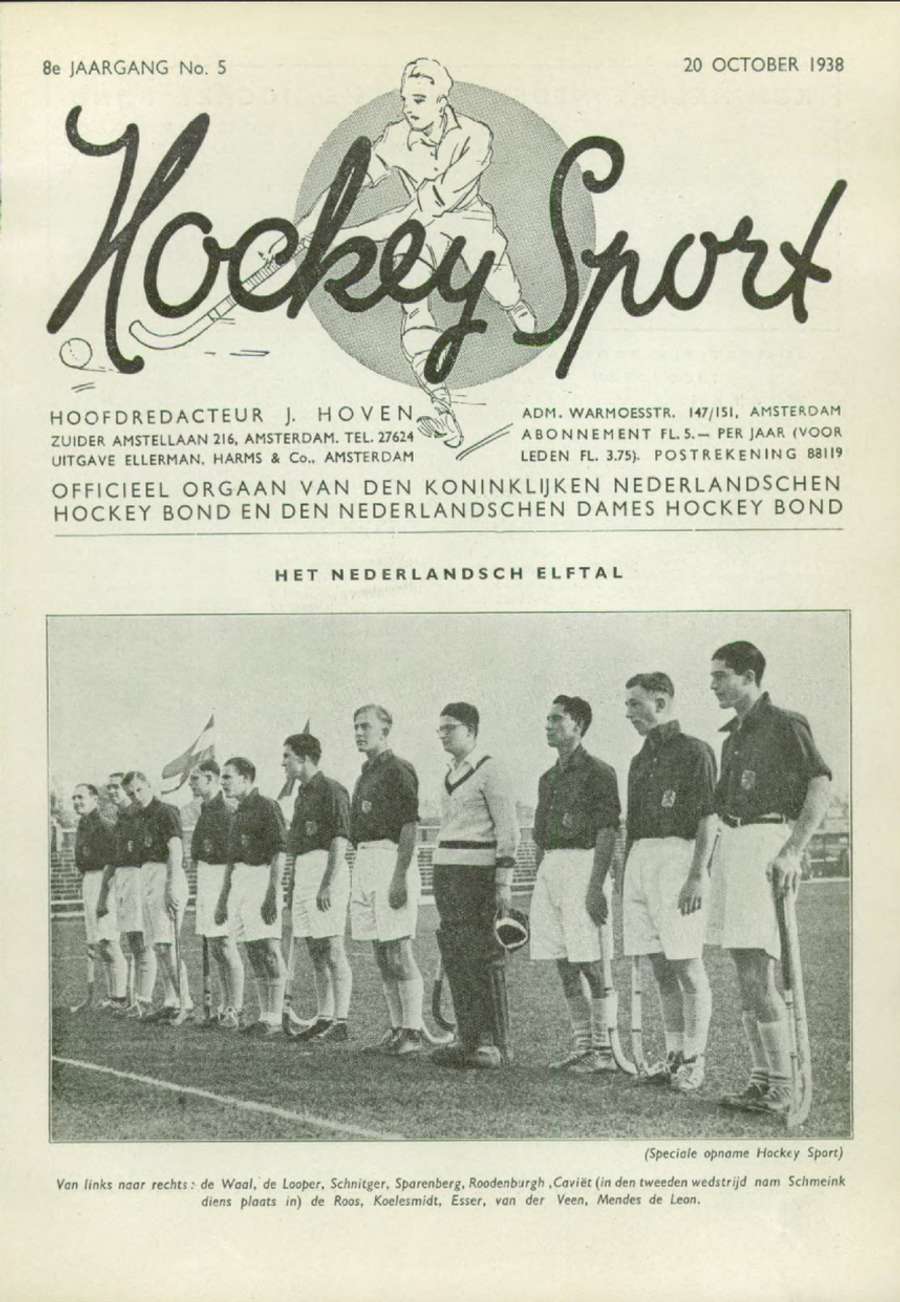

The boy Piet even got the opportunity to play for Ajax himself, but instead Roodenburgh chose hockey in the field. It turned out to be a wise choice, as Roodenburgh, who played his club matches in Amsterdam, soon grew up as one of the most popular hockey players in the field – a reputation that gained his international debut.

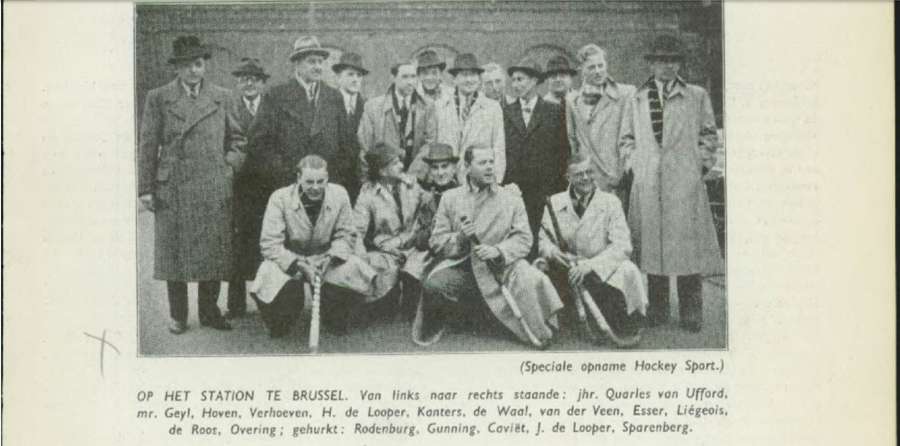

Piet was living a sustainable, promising life in Amsterdam when Nazi Germany occupied the Netherlands on May 10, 1940. Five days ago, Roodenburgh played what he ended up being his eighth and last match for the National Hockey team in the Dutch field-a 4-3 loss to the Belgian in Brucels. Roodenburgh, a right forward, was described as an insufficient productive virtuoso from the magazine HockeyBut he scored twice in his seventh match for the Netherlands.

Resistance

The war did not change much for Roodenburgh. He stayed at school and continued to play hockey on the field for Amsterdam, but everything changed in 1943.

When Roodenburgh graduated from the University of Amsterdam in April 1943, the 25-year-old refused to sign the German oath of loyalty, who stated that the subject was to refrain from actions against German Reich, German Armed Forces and Dutch authorities.

Of the 14,600 students who were told to sign the oath, 12,400 rejected and endangered serious consequences. 3,500 students were arrested and sent to Germany as forced workers for refusal to sign the oath, and nearly 9,000 students were hidden.

Roodenburgh was one of them. The latest article registered on the ground citing Roodenburgh was published in April 1943, when Piet was elected to the provincial team of North Holland. “Rapid and technical right forward” took more serious measures to stay outside the hands of Nazi Germany and tried to flee to England.

After getting into trouble in France, Roodenburgh deflected in Switzerland and washed a heavy snowstorm, which was almost fatal to reach neutral land.

After there, Roodenburgh spent time in an internment camp before contacting Dutch General Aleid Gerhard Van Tricht, who hired the Hockey Hero as a courier for Fiat Liberas-Group GM, a group of spies employed by the Dutch government in London.

Dutch spy

Roodenburgh brought valuable information back to Bern, where he would be sent to the Dutch government in exile. A roodenburgh stole Intel, was the German V-1 flying bomb.

Roodenburgh took his information with him on the Swiss road, part of the Dutch-Paris escape line. Roodenburgh would also take some people in need to return to Bern during his trips.

Now a resistance fighter, Roodenburgh, stopped in his footsteps when Allied forces occupied Normandy on June 6, 1944, best known as D-Day. The occupation has made it impossible for the Dutch-Paris escape line to continue working, forcing Roodenburgh to make a career switch.

The former Hockey International Dutch returned to the Netherlands under the Harms alias PC and joined the Amsterdam fighter group. Roodenburgh was involved in the departures of allied weapons and sabotaged the German war machine, but also took on a key role in the internal resistance control service, which tracked and collected information about renowned NSB party members and Nazi German employees SicheritsDienst, secret intelligence agency.

Tragic destruction

An Intel fed in Roodenburgh would have catastrophic consequences. The detective group of resistance group took Roodenburgh in contact with Nazi collaborator Wim Henneicke, the head of Colonne Henneicke, a group of Amsterdam -based Jewish hunters. Henneicke betrayed Roodenburgh and arrested the Café Dubois resistance fighter, south of the city center of Amsterdam.

Following his transfer to the detention center near his arrest site, Roodenburgh would soon be put on a list of deaths – a new measure the Nazis had taken to clear prisons and take pressure from the courts. Anyone who entered a list of deaths was named ‘Death Candidate’ and would be executed as a form of revenge on resistance acts. A crowd would be forced to look and the bodies would not move for 24 hours to give a signal.

Just a month after his arrest, Piet Roodenburgh’s life would end this in this correct way. After members of the resistance explode a German Nazi ammunition train in Witgeest, North Netherlands, Roodenburgh and two other candidates were shot dead in the exact site of the train attack. Former former field hockey and the future face of the national team died at the age of 26.

Piet Roodenburgh never experienced the freedom he fought to arrive, but was honored after his death. In 1949, Queen Wilhelmina gave Piet Roodenburgh Lion of Bronze – one of only 1,210 people to get this medal. Roodenburgh took the medal to be someone who “He has distinguished himself in the fight against the enemy by engaging in particularly bold and caring acts.”

Magazine Hockey also honored Roodenburgh after the war, profiling the felt international as “The right of the Dutch national team who became a real hero, who made the place a great service and finally executed for betrayal. This excellent athlete will be remembered with gratitude.”

And where Roodenburgh was first buried in a mass grave at the behest of the Nazis, the resistance hero was laid to rest in the Dutch Blomendaal Honor Cemetery, where his tombstone sends a powerful message: “Freedom of the mind overcomes time and death.”